The Coast Survey maps of slavery: new discoveries!

In April I was privileged to deliver the Vorhees Lecture in the History of Cartography at the Library of Virginia. Our theme was Civil War mapping, and the Library organized a wonderful one-day exhibit of its relevant maps to complement my talk. Scholars of Virginia and mapping surely know the names of Marianne McKee and Bill Wooldridge, both of whom have authored splendid books on the subject. both of whom attended the talk and shared their expertise with me.

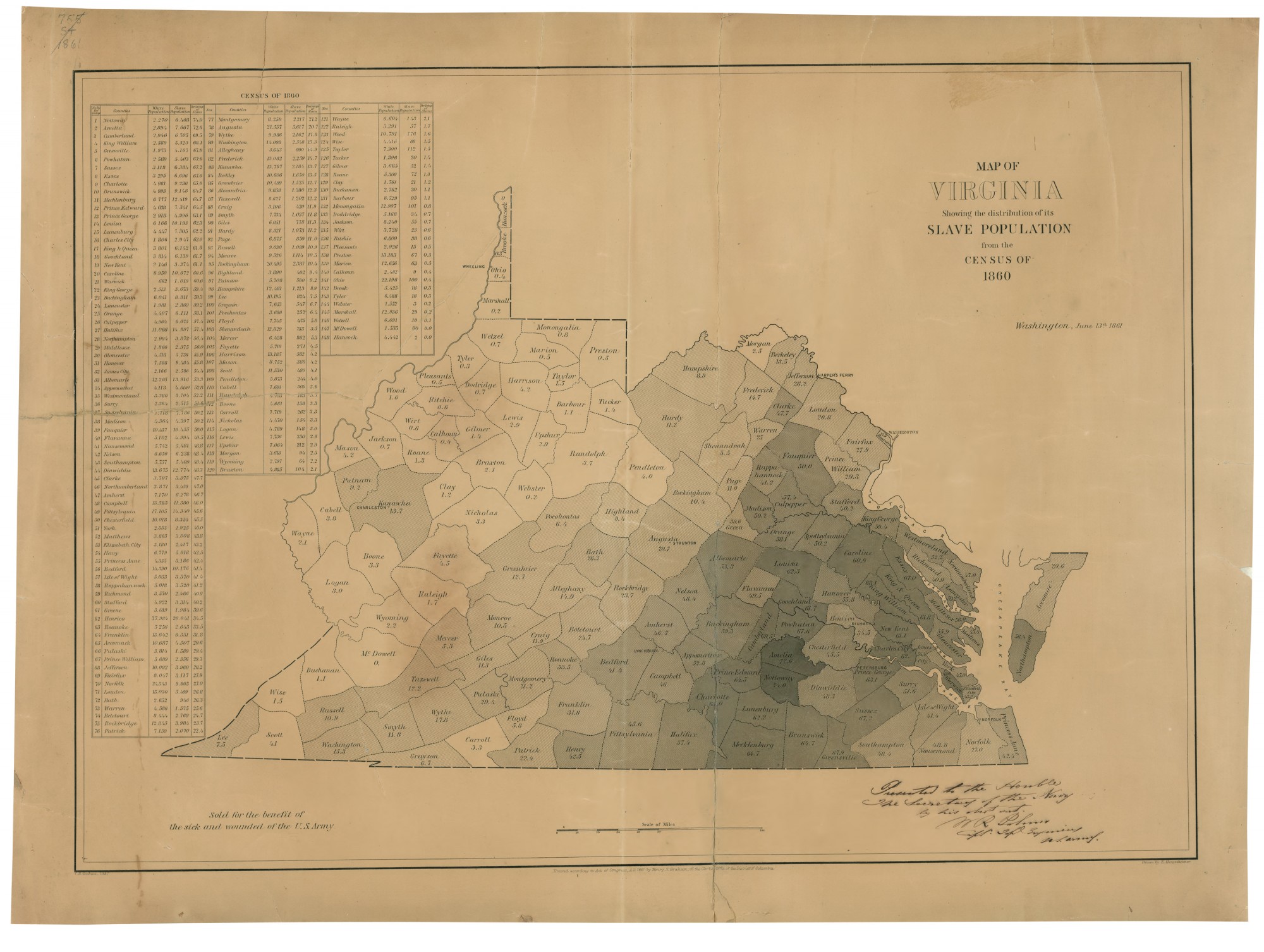

Out of those discussions came a discovery about the Coast Survey maps of slavery that I have written about online and in chapter four of Mapping the Nation. The first of these was published in June 1861, a path breaking attempt to translate census data into cartographic form, and an example of the Coast Survey’s experimentation with new methods of visual representation and shading techniques. Here is a copy from the Library of Virginia’s own collection.

I’ve argued that the map was created for several purposes, one of which was to influence Virginia’s own future in the early days of the war. At the moment the map was issued, General George McClellan had brought the Department of the Ohio into western Virginia in order to secure the Ohio Valley. By stabilizing the region this also allowed voters in that region to convene in Wheeling, and move forward with their own plan to secede from Virginia and form an eventual state of West Virginia, which remained part of the Union during the war.

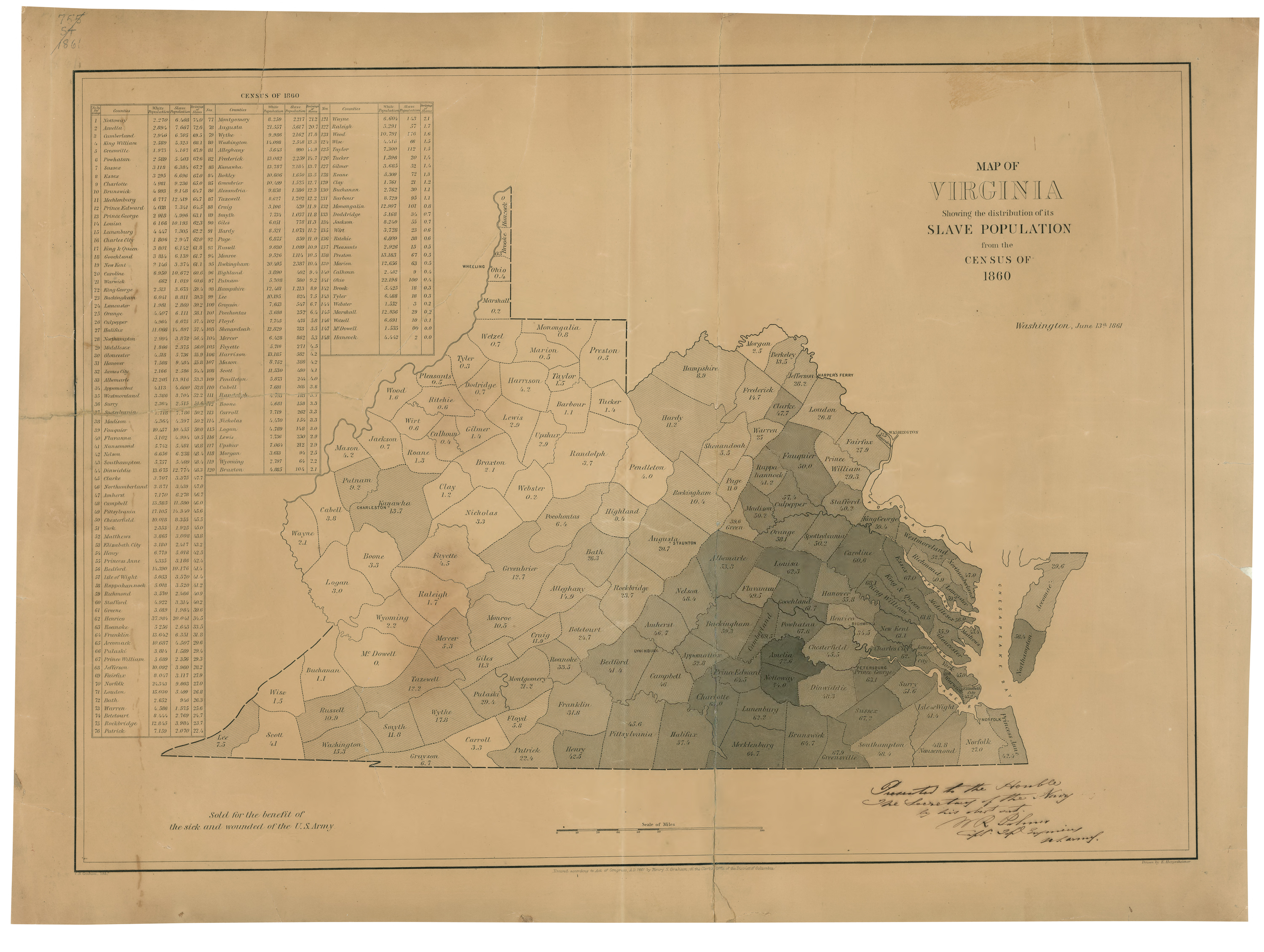

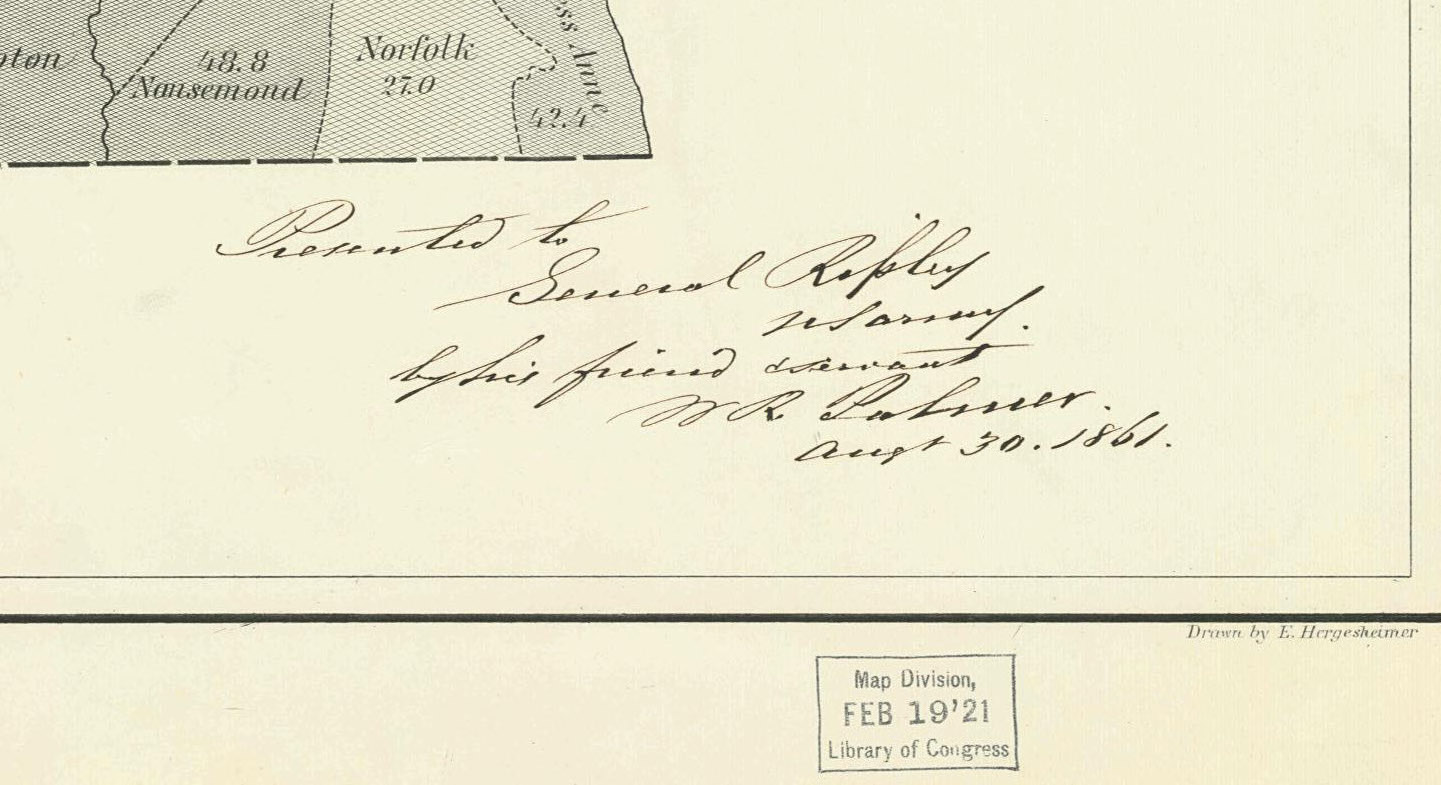

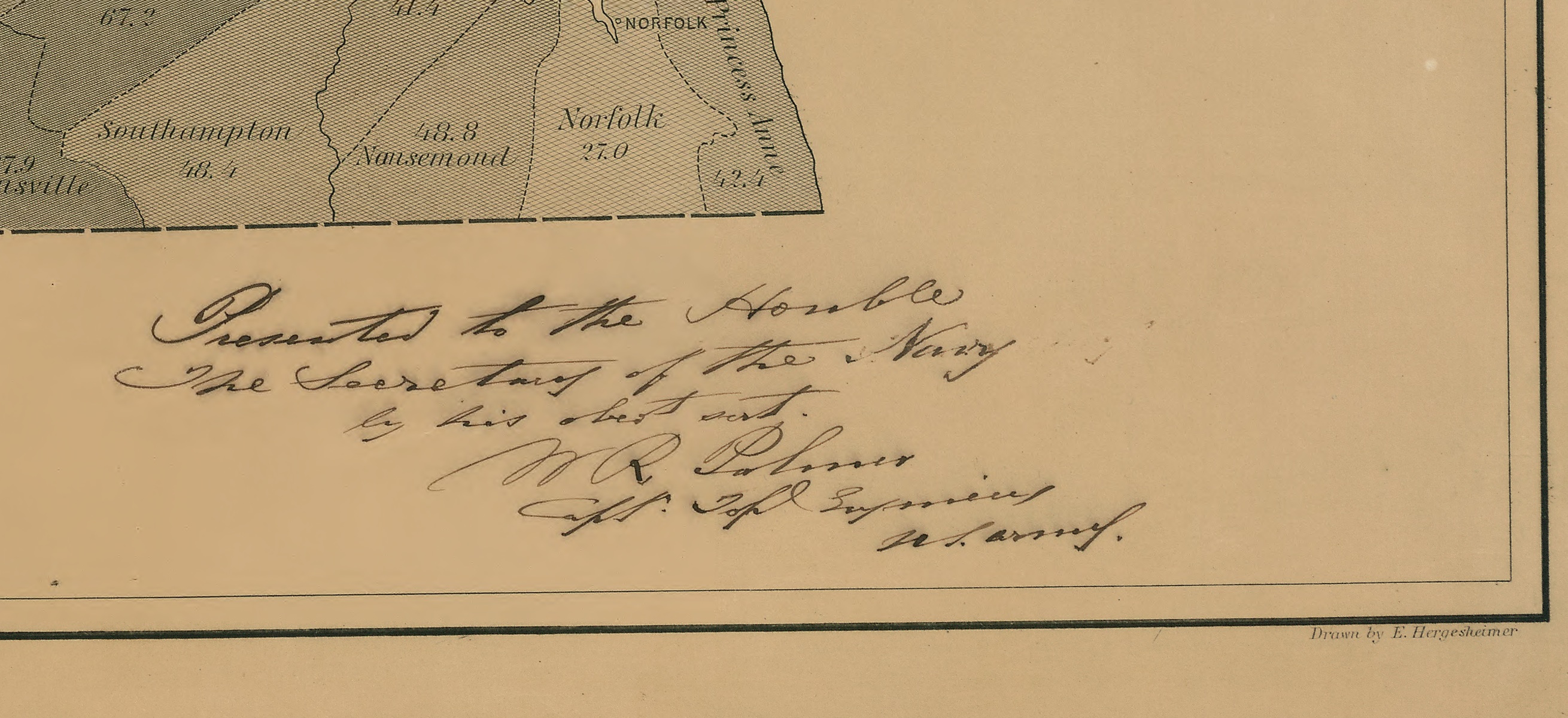

The map also had a potent life in the nation’s capitol and within the Union military. We know this thanks to the fact that I’ve found several copies of the map (at the National Archives and the Library of Virginia) with inscriptions in the lower right corner. These are all written in the same hand of William Robert Palmer, a captain with the Corps of Topographical Engineers who had worked with the Coast Survey for several years by the time the map was printed in the summer of 1861. Palmer gave copies of the map to the Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, as well as Army Generals Ripley and Totten. I took this as confirmation of my sense that Palmer had been deeply impressed by the experimental work going on at the Coast Survey’s mapping division. Here are two of the inscriptions, in Palmer’s hand.

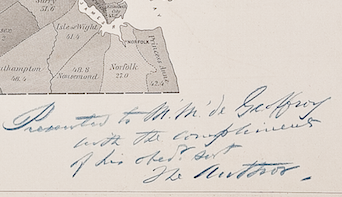

But when I came across another copy of the map in Wooldridge’s Mapping Virginia, my understanding of the map and Palmer’s role became more complicated. In the lower right corner of this copy, in Palmer’s hand, is an inscription that gives us new insight into the significance and reach of the slave map of Virginia. Take a look for yourself at his inscription to “de Geoffrey,” who was the French Charge d’Affaires in the United States during the war.

This inscription raises two important questions. First, note that Palmer refers to himself as “the Author.” This suggests that he had a far more important hand in the creation of the map than I previously imagined, and was actively participating in the new print and representation techniques that led to these incredibly important maps of slavery during the Civil War.

Second, by giving the map not just to military and political leaders, but to foreign diplomats, Palmer seems to have considered the map of importance to the meaning of the war abroad. I have long acknowledge the persuasive, even propagandistic power of these maps for their ability to represent the distribution of slavery across the south. President Lincoln acknowledged the power of the map of southern slavery, and I believe it influenced his understanding of both Confederate and Unionist sentiment in the south. But to learn that the map was also distributed to at least one foreign diplomat suggests that it might have persuasive power abroad.

This is particularly intriguing given the timing — the Lincoln Administration desperately needed French and British support during the war. More accurately, the administration needed the French and British to refuse recognition to the Confederacy. Such a map like this may not have been created for that purpose, but Palmer seems to have believed that it could only help the Union effort in this regard.

Special thanks to Bill Wooldridge for his superb Mapping Virginia, and to the Virginia Cartographical Society for permission to post its copy of the Virginia slave map of June 1861.

Use controls to zoom and pan.

Dear Dr. Schulten,

I have seen this map a number of times used to explain the creation of West Virginia, but I’m afraid it is not that easy. I can see the temptation inherent in the map, but the map does not explain the vote, in West Virginia counties that have almost no slaves, to secede from the United States along with the rest of Virginia. The slave map above has no relation to the rending of Virginia, which in actuality was a grand scheme of political opportunism by the Union war governor Pierpont and his supporters. The relative lack of slaves in the west was one of the excuses used by Pierpont but one must always be sceptical of the motives of militarily supported minority governments in their claims over territories and people. The arrest of thousands of West Virginians by Pierpont and Union authorities and the fact that the greater part of West Virginia supported Virginia rather than the Union gives the lie to Pierpont’s claims of West Virginia loyalty. In fact, Pierpont’s push for statehood actually betrayed the interests of the Union in western Virginia because most West Virginians did not want a state of their own. On Dec. 30, 1862 Pierpont telegraphed Lincoln with a message beginning “The Union men of West Va were not originally for the Union because of the new state.” The telegram is in the Library of Congress Lincoln collection. So, in fact, Pierpont was working against Union interests. The creation of West Virginia really had nothing to do with the war, it was a bit of private enterprise which to this day remains unrecognized by historians.

If you go to the Wikipedia article “Appalachia”, in the subsection “The U.S. Civil War”, you will see a map I created from the records of the secession conventions of the deep South states and the popular votes in Tennessee and Virginia on secession. I used this same map.