Mapping Sherman’s March

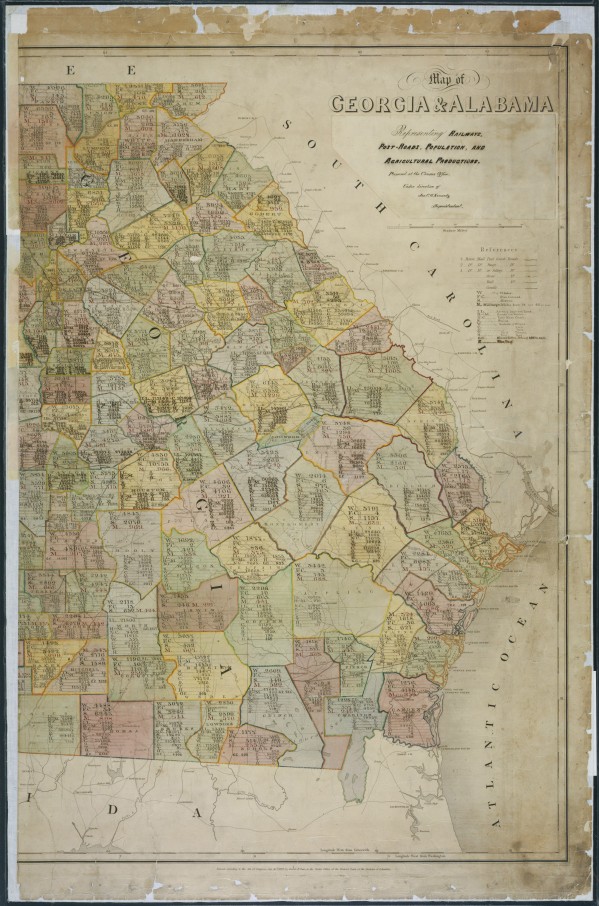

I recently came across one of the earliest attempts by the Superintendent of the Census to incorporate census data onto a map, made during the Civil War.

The map is undated, though the National Archives assigned a rough date of 1864. It may be slightly earlier.

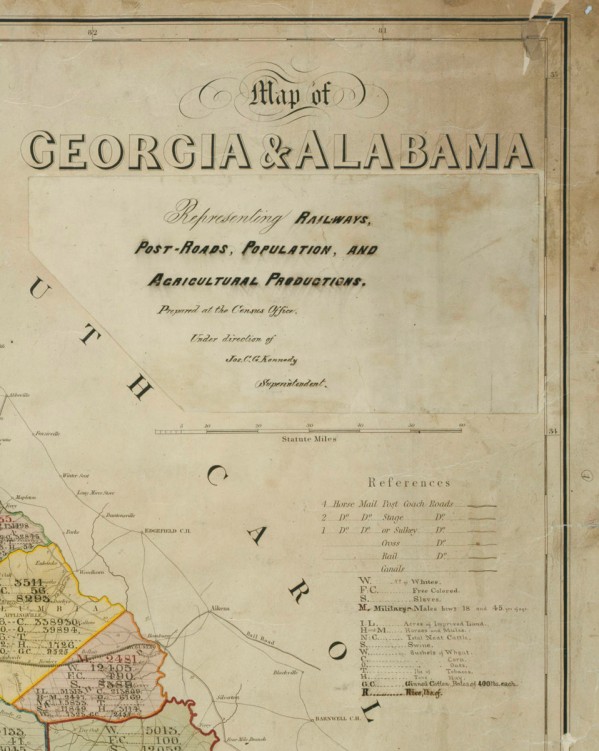

This is an adapted portion of a larger map of Georgia and Alabama originally issued in 1839 by David Burr. The map is annotated with 1860 Census data by then Superintendent of the Census, Joseph C.G. Kennedy. I discuss Kennedy at length in chapter 4 of Mapping the Nation, for he was at the forefront of the general excitement about the promise of statistical analysis in the 1850s. But for all his enthusiasm for statistics, Kennedy does not seem to have attempted to map data in any systematic way prior to the war, though he was aware of and appreciated the path breaking efforts to map population data both in Europe and the United States.

Kennedy simply took Burr’s 1839 map and added data that would be useful for military operations in Georgia. Notice that he identifies agricultural output, livestock, and population, including men of military age as well as the number of slaves and free coloreds in each county.

Kennedy was still not mapping the data in any dynamic sense, but rather simply listing relevant statistics. Still, it is a telling glimpse inside the war, and gives us some sense of his efforts to turn the Census toward military purposes. Here is a close up of central Georgia, the heart of Sherman’s traverse in the fall of 1864.

I came across the map through Herman Friis’ excellent article, “Statistical cartography in the United States prior to 1870 and the role of Joseph C.G. Kennedy and the U.S. Census Office,” from The American Cartographer v.1 (1974). Friis was the former head of the Cartographic Division of the National Archives. He found this map, but it’s not entirely clear whether it was part of a larger effort to map data throughout the Rebellion. I’m now searching for other examples in the National Archives: because they were unique items they don’t seem to appear in the Library of Congress or other repositories.

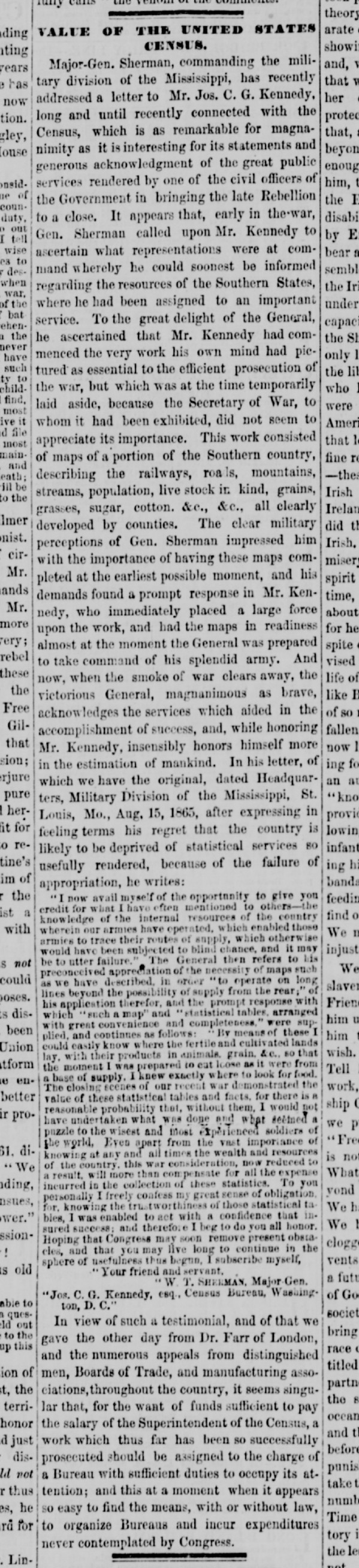

It appears that Kennedy was working to map data in this way during the early part of the war. In The American Census, Margo Anderson explains that in January 1862 Congress passed a resolution authorizing Kennedy to report statistics directly to the War Department. Yet his efforts to map this data seem to have gone relatively nowhere. Then, General Sherman asked Kennedy to provide relevant data as he prepared his march through the southeast, so the effort was revived. I found an intriguing article in the New York Daily Tribune from August 1865, citing Sherman’s appreciation for these maps in his wartime march through Georgia. The maps and data were invaluable, Sherman writes — among other things “I knew where to look for food.” He goes on to say that without the data found on the map, “I would not have undertaken what was done.”

Sherman concludes with a plea for increased postwar funding for the Census Office. This fell on deaf ears until the next Superintendent, Francis Amasa Walker, was able to brilliantly demonstrate the relevance and power of the data through maps.

There is much more to this story that I need to figure out. For instance, I’m currently researching the role of Orlando Poe, the engineer who had done so much to secure Knoxville for the Union in the fall of 1863. Based on that achievement, Poe was tapped by Sherman to be his chief engineer, and subsequently made extensive maps of Georgia to prepare for the march. More soon!

Use controls to zoom and pan.