Mapping the Paris Peace

This week marks the hundredth anniversary of the Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919. From January to June, the great powers met at Paris to replace the imperial order with one that reflected a welter of interests and contradictions, not least of which was Woodrow Wilson’s aim to make the world safe for democracy.

Most of the key decisions regarding territorial reorganization were made in January 1919, the first month of peace negotiations, and they hinged on maps. But the maps that informed the Treaty of Versailles were not just ones that redrew borders and boundaries; new thematic maps–ones that profiled ethnic population, linguistic groups, religious identities, agricultural regions, railroad networks, and the like–enabled negotiators and advisors to think differently about a “just” peace in Europe.

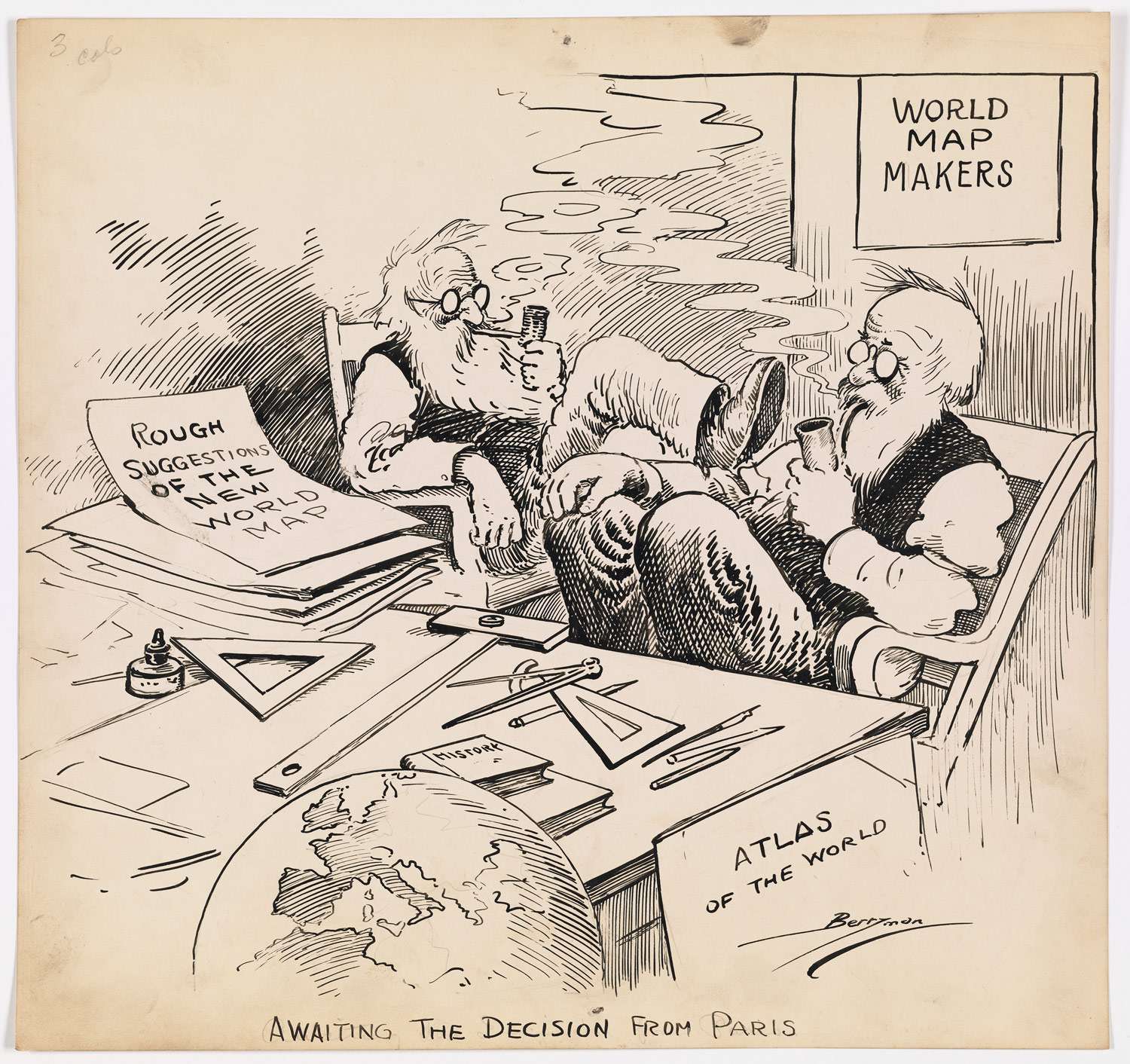

John Berryman’s January 1919 commentary on the opening of the Paris Peace negotiations after the Great War. Courtesy National Archives.

More specifically, within months of the U.S. entry into the war, President Wilson authorized a group of experts to influence the postwar peace. These men, collectively known as The Inquiry,” produced thousands of reports and maps used at Paris to redraw European borders. By late 1917, Isaiah Bowman boasted that the Inquiry could create any map needed for peace negotiations in a matter of hours. Such a statement would have been unimaginable even a few decades earlier, but is a matter of course in our own age of digitally driven mapping.

On one level, such data driven research reflects Wilson’s idealistic sense of the American position as free of politics and national interest, seeking a more “neutral ground” for a true and lasting peace in the wake of the old imperial order. Yet Wilson’s approach also reveals the presumptions of American power, even in its infancy. Consider his plea to his advisors while crossing the Atlantic: “Tell me what is right and I’ll fight for it; give me a guaranteed position.” With enough data, Wilson and his emissaries believed they might overcome centuries of imperial conflict and a diplomatic order grounded in the balance of power.

In place of that old order, Wilson hoped that peoples might be aligned with nations. Thus for the Inquiry Committee, the central questions were “where do people belong” and “where do national borders belong?” In other words, Wilson’s advisors equated national identity with ethnic predominance. And that thinking was made possible by a new kind of map.

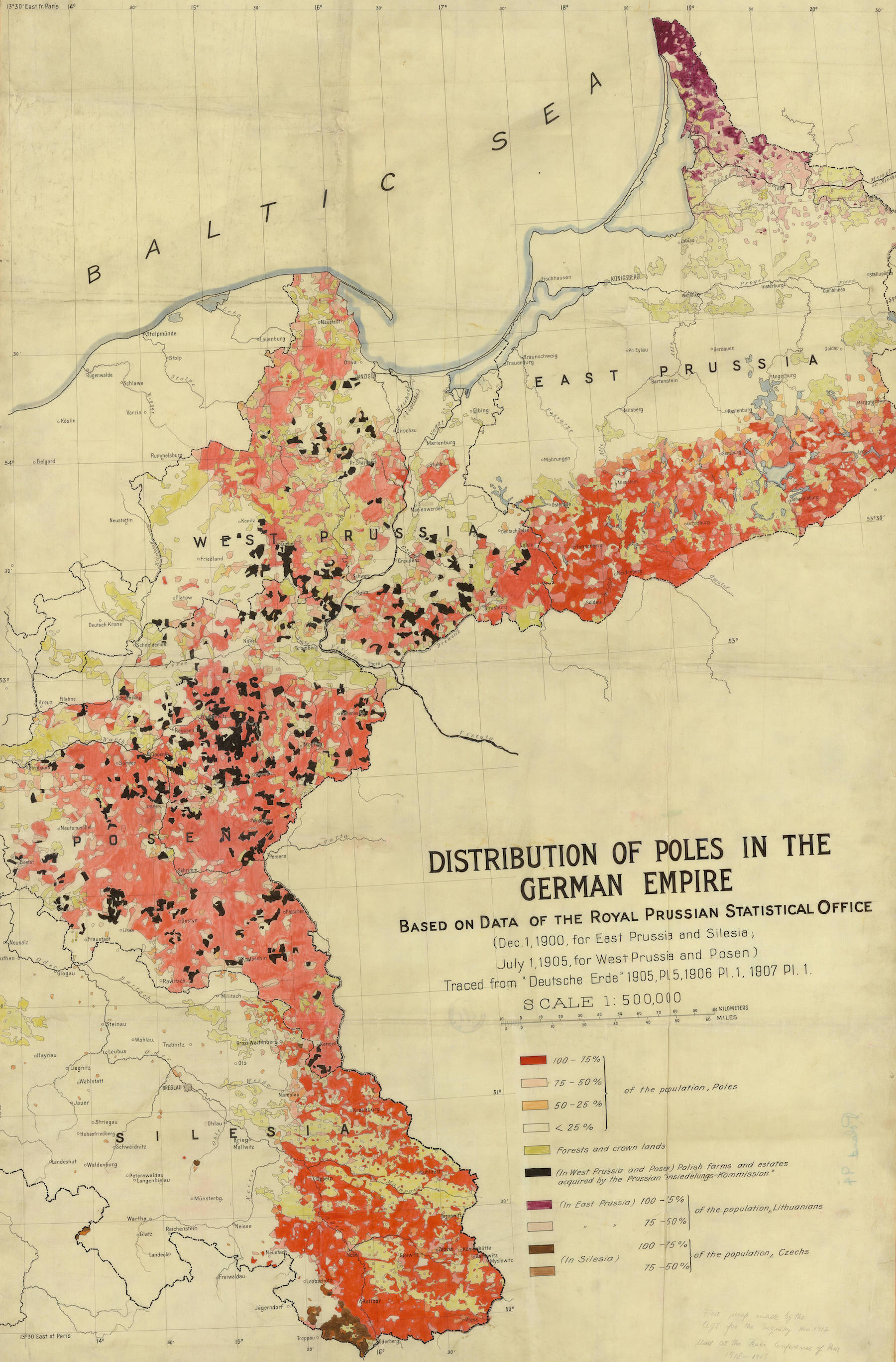

Consider the first map made by the Inquiry, a full year before the armistice and well before Wilson identified a free and independent Poland as part of his Fourteen Points. The map uses a relatively new technique of profiling the ethnic population in order to argue that these areas form a reconstituted Poland. Much of this area became the Polish Corridor, emptying at the city of Danzig on the Baltic Sea. Far from determining the American position, though, the reflects the preexisting sympathy among Wilson’s advisors for Polish independence. In this case, Wilson’s principle of ethnic self-determination aligned with the Inquiry’s goal of supporting Polish territorial claims.

Among the first maps made by Wilson’s advisers, in November 1917, to prepare for the reconstitution of Poland. Courtesy University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee.

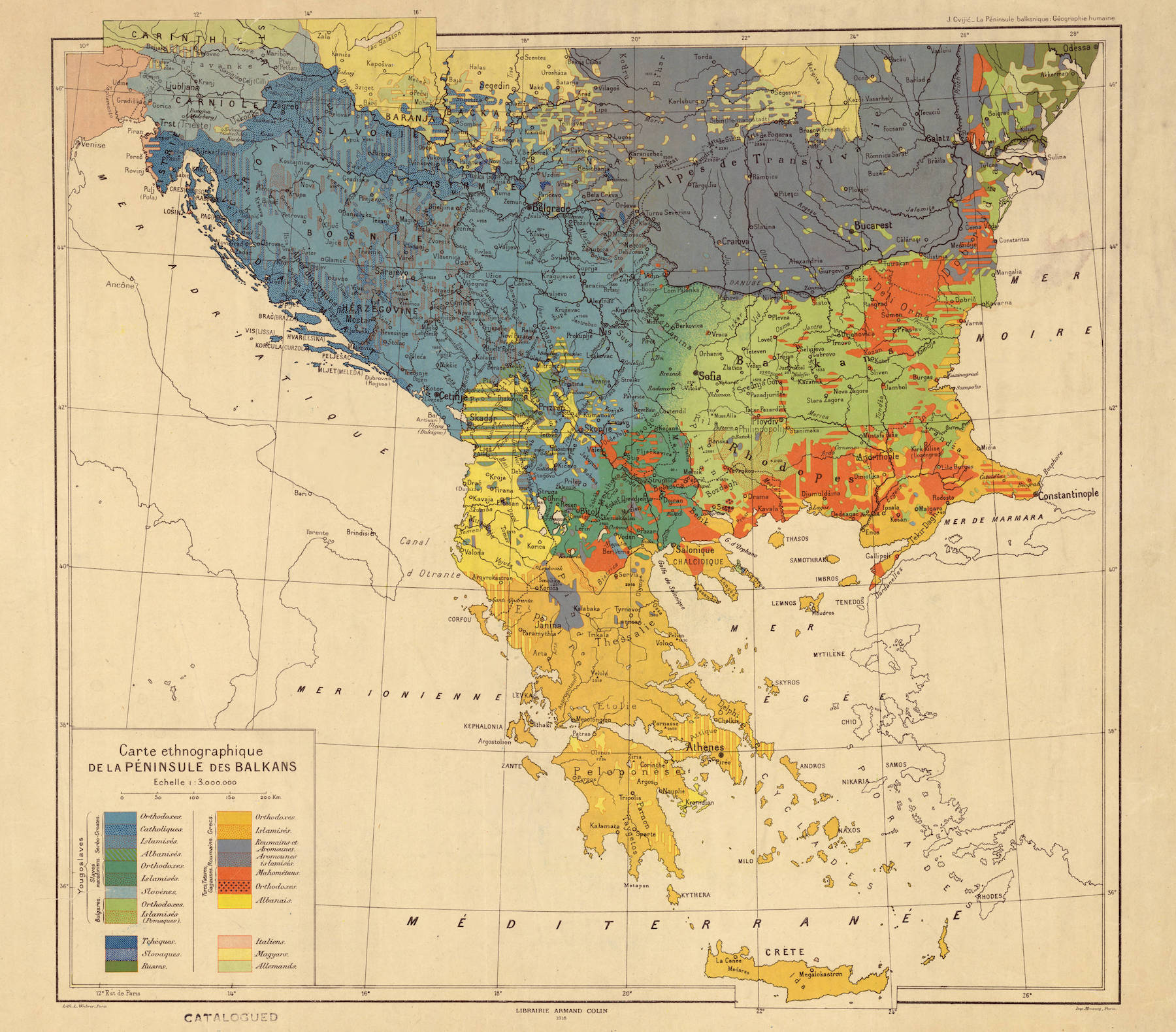

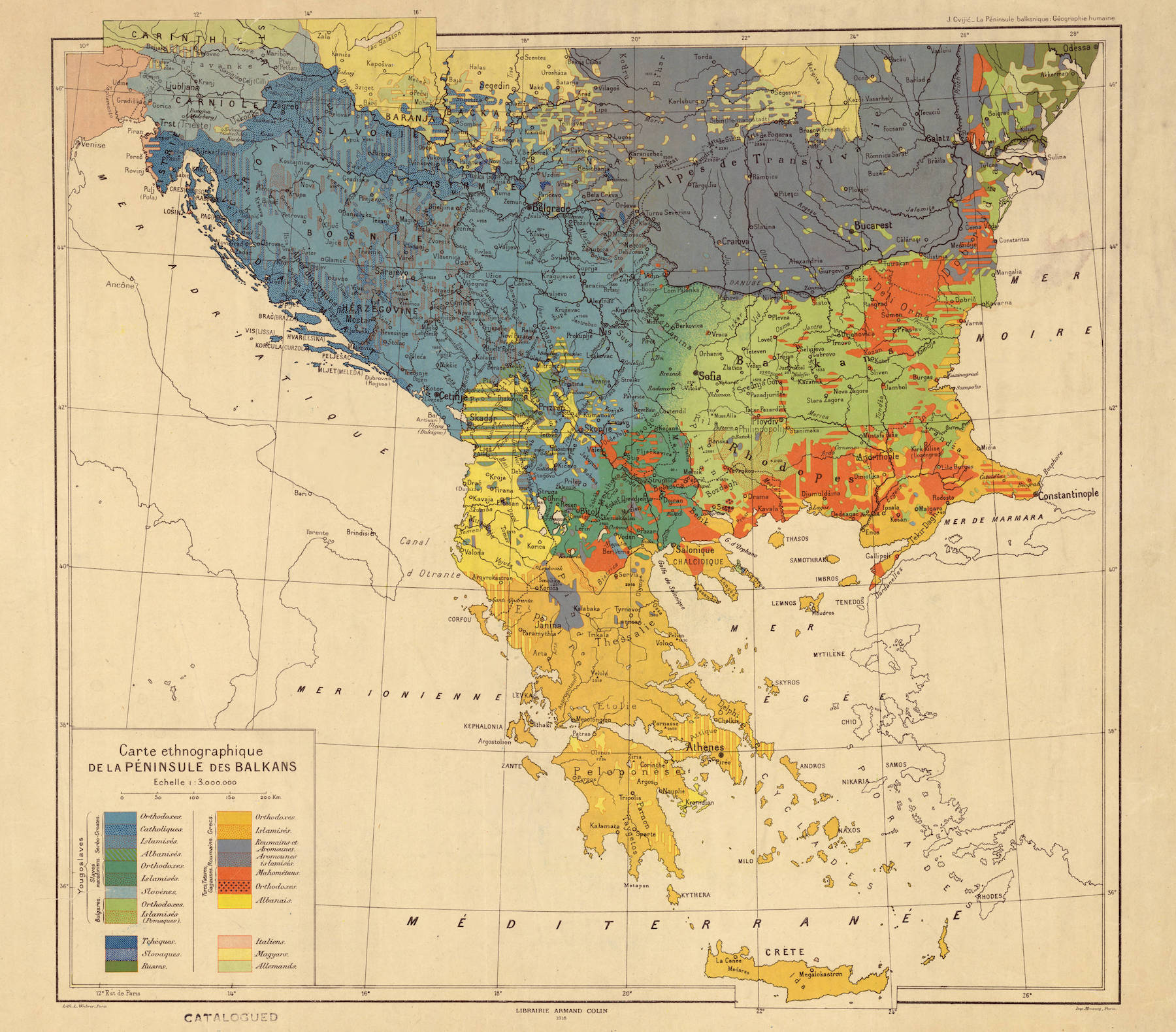

Similarly, the Inquiry was particularly riveted on the “storm center” of ethnic groups across southern Europe. The Slavic geographer Jovan Cvijic supplied this map to the Inquiry, which used cutting edge mapping techniques to identify the predominant ethnic and religious identities of the region in a way that suggested a coherent Yugoslavian nation. Of course these “racial” categories on the map were deeply contested even then, but the key is the way the map represented a new kind of language and thinking.

A map used by the American peace negotiators to argue for the coherence of a new Yugoslavian nation, grounded in ethnic and religious identities.

Note the blue areas that border the Adriatic to the west, which Cvijic argued was the basis for a united Slavic nation. That same “uniformity” of Slavic identity reinforced American opposition to Italy’s claim to Fiume and other places along the Adriatic coast. While the Italians argued that Fiume was “culturally” Italian, the Americans used maps such as this to counter that ethnically the region belonged to Yugoslavia.

Isaiah Bowman recognized that these maps were tools of power, subject to manipulation and abuse as maps had always been. As he wrote, a map is both “a picture and an argument,” and the welter of interests at the peace each used maps to buttress prior aims.

The ironies here are real: with the goal of making the world safe for democracy, and striving for national self-determination, Wilson and the other leaders at Versailles organized and reorganized political entities in a way that bred anti-democratic movements. Fiume became a point of reference for the resurgence of Italian nationalism in the 1920s, while Germany invaded Poland once again in 1939. The peace negotiations of 1919 turned on a language of maps that was new, but a language of power that remained unchanged.

Sources: Margaret MacMillan, Paris 1919: Six Months that Changed the World (2002); Jeremy Crampton, “The Cartographic Calculation of Space” (2006); Lawrence Gelfand, The Inquiry (1963); Susan Schulten, Mapping the Nation: History and Cartography in Nineteenth Century America (2012); Mirela Altic, “The Peace Treaty of Versailles” (2016).

Use controls to zoom and pan.