Mapping early Colorado and the University of Denver

On February 25 I delivered an address on the University of Denver campus to commemorate the 150th anniversary of our institution. My goal was to go beyond the history of the university and instead tell a more complex story about how the institution came to exist in the first place. The entire address is available here (and yes, I’m aware that my collar is crooked…). Happy birthday to DU!

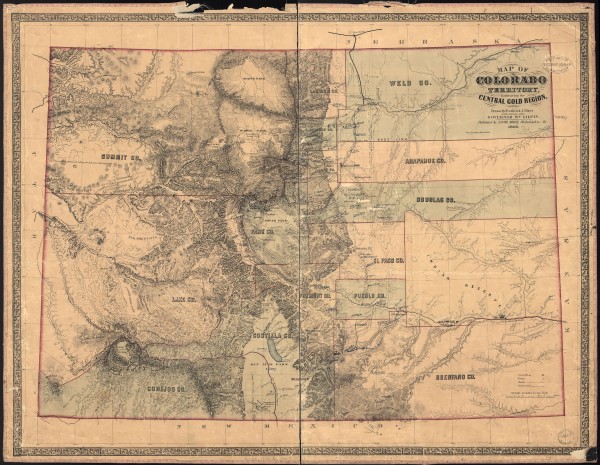

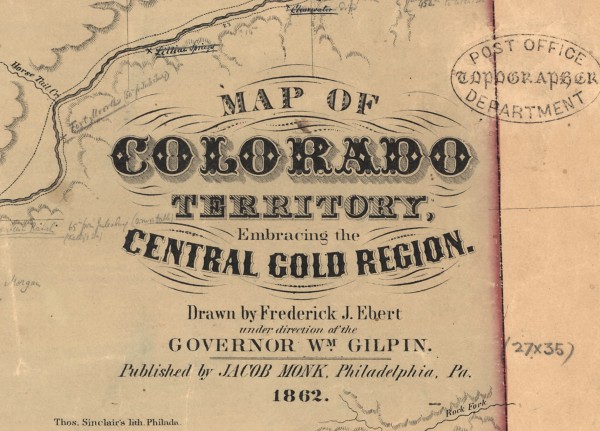

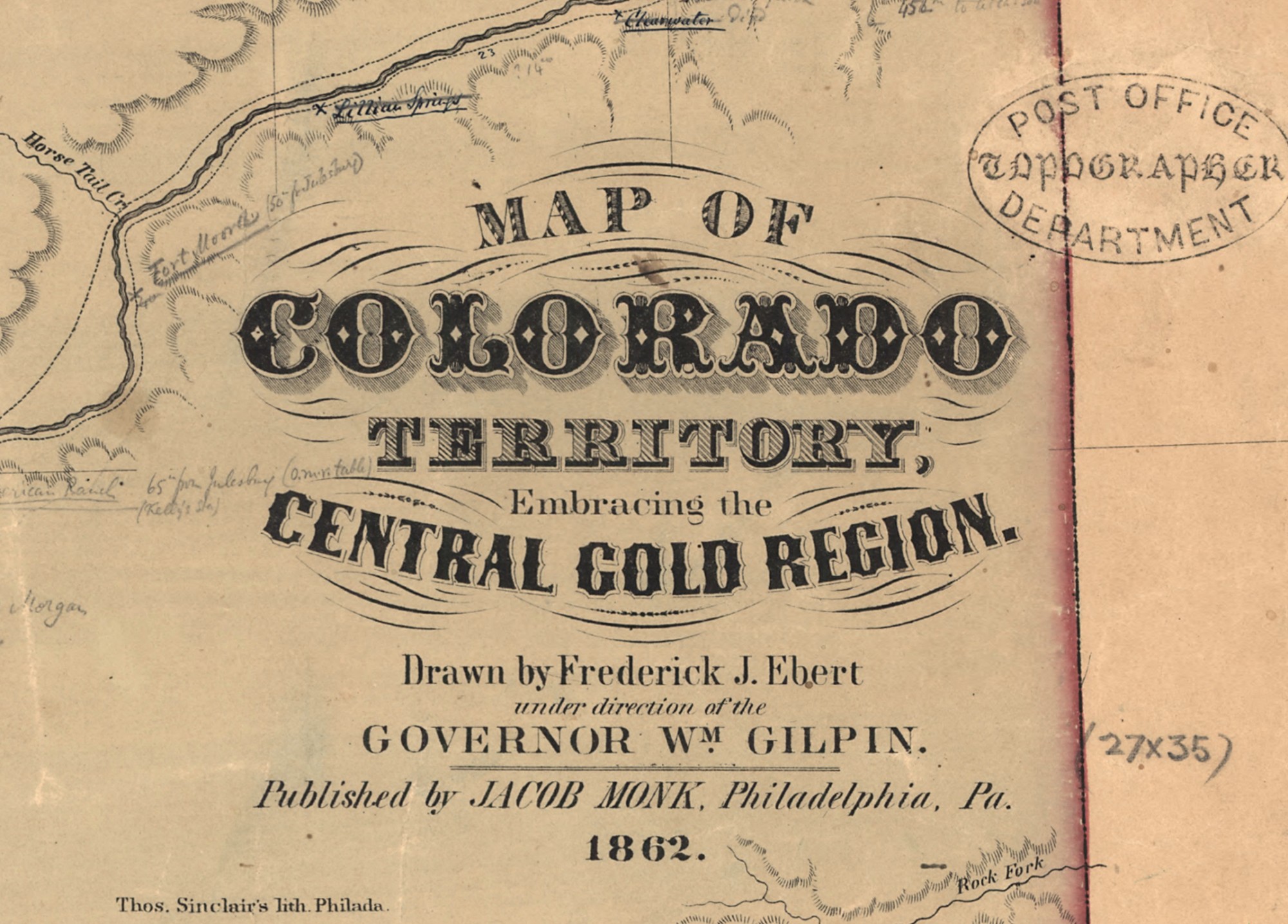

To do this I drew heavily on maps, especially the first authoritative map of the Colorado Territory, made in 1862 under the direction of the first territorial governor, William Gilpin, and drawn by Frederick Ebert. There are just a few copies of this map known today, and I focused on one in the Library of Congress that was used by the post office, probably in Denver. It includes extensive annotations regarding new town sites, distances, and proposed Indian reserves. Ebert undertook the map just after completing the first railroad survey in the territory, between Denver and Central City, in 1861.

The map includes a high level of detail–so much so that we might question its reliability. After all, much of this topographical detail was simply unavailable in 1862, though in some areas it comes fairly close. You may also notice a rather large (and non-existent) lake in south central Colorado, within Costilla County. Again, an indication that much of the topography of the more remote areas was speculative and aspirational. But that aspirational aspect was part of the very goal of the map: William Gilpin had a long history as a booster for the region, and you can see his enthusiasm in the title of the map itself, “embracing the central gold region.”

I also like the way the Ebert-Gilpin map captures the fragility of Denver at the moment that President Lincoln replaced Governor Gilpin with John Evans. Evans had a strong reputation within the Republican Party–indeed he founded the party in Illinois–and had been heavily involved in railroad investment in and around Chicago. He also founded Northwestern, and is the namesake of its home in Evanston.

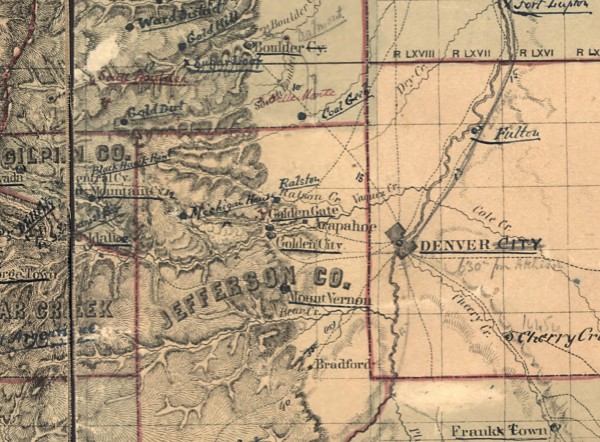

When Evans arrived, Denver was facing a declining population, serious conflicts with the Arapahoe and Cheyenne tribes, an evaporating mineral rush, and an uphill battle to get a railroad to connect the town to the outside world. Indeed, take a look at the detail below, and notice that the post office has written “630 miles from Atchison” just below “Denver City,” an indication of just how far the small town was to the nearest major mail outpost toward the east.

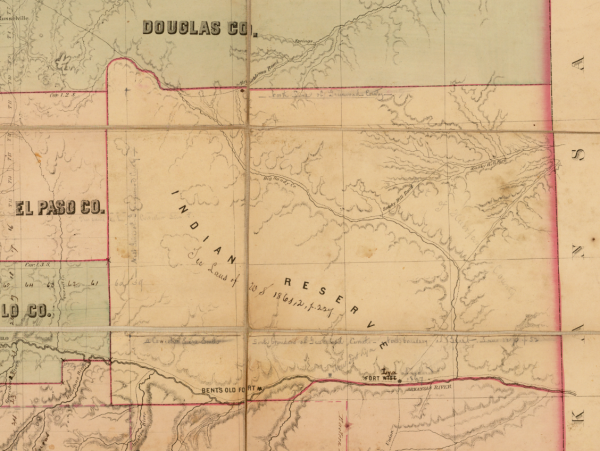

The map also includes a large “Indian Reserve” to the southeast of Denver, a product of the recently concluded Treaty of Fort Wise. This is especially important information given the ongoing (and escalating) conflicts with the plains tribes and Denverites during the Civil War. This is a complex history that others have covered well, especially Elliott West in Contested Plains. Here I simply want to note the presence of this “Reserve” on the map–which is itself rare given that it only existed between 1861 and 1864.

The map is the first to show counties in Colorado, and in my view suggests a level of stability and political organization which is utterly at odds with the turmoil “on the ground.” Carl Wheat, in his exhaustive history Mapping the Trans-Mississippi West, calls the map “imposing,” and it certainly conveys a sense of permanence in a territory which is less than a year old, and which has only a few thousand inhabitants. Notice the number of towns that have been introduced, and subsequently deleted (all of the notations on this map would have been made within just a few years of its being printed).

All of this raises the question: why did Gilpin make the map? Was he hoping to attract capital to the territory? Settlers? Why did he feel the need to go beyond the other extant map of the region produced by the General Land Office? The latter was a much more restrained document–one that shows neither counties nor many towns. Perhaps the GLO map simply failed to portray Colorado in the way that Gilpin wanted: as a territory that was ripe for development, safe for settlement, and a perfect destination for the next wave of railroad development.

Devoted historians of Colorado (and maps) will be impressed to learn that another copy of the Ebert-Gilpin map has *just* resurfaced in the family papers of Ebenezer Wells, the author of the Territorial Constitution. Barry Ruderman has done some terrifically detective work and historical research on the map, which he has for sale here.

Use controls to zoom and pan.