Lincoln, maps, and the invasion of East Tennessee

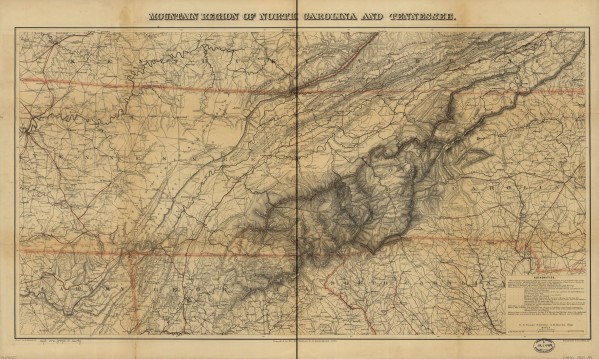

In the spring of 1863–exactly 150 years ago–the Coast Survey was in the midst of an effort to comprehensively map the rebellion on a series of regional maps at a scale of 10 miles to the inch for use by commanders in the field. John Cloud, an affiliate of the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration (which subsumed the Coast Survey) drew my attention to one of the maps that stood out for its particularly high level of detail: The Mountain Region of North Carolina and Tennessee. Here is the 1863 edition from the the Library of Congress.

The map has a fascinating history that is embedded in the turmoil of the war and especially the campaign to invade Tennessee. The very fact that the Coast Survey had mapped the rebellion in such great detail indicates how much it had expanded its original responsibility–charting the coastlines and inland waterways.

But this region posed the particular challenge of making sense of the complex mountain system of the southern Appalachians. To do this in the midst of the war, without access to the terrain itself, the Superintendent of the Coast Survey urgently called upon Arnold Guyot, the nation’s leading expert on the Appalachian Mountains. Guyot had spent several summers in the late 1850s exploring the region, compiling detailed records about the geography of the system. He responded to the Superintendent with a lengthy report on the region.

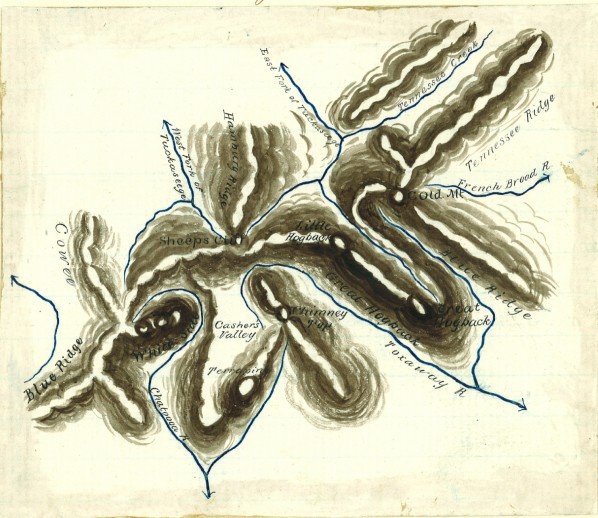

Among his more interesting insights was that the southernmost reaches of the mountains were unique in the system: while the mountains lie in parallel ridges to the north, in Tennessee and North Carolina they twist and turn into interlocking ridges. He took pains to draw–elegantly–the relationship between a few of these ridges in the southwestern corner of Tennessee for the Superintendent. Guyot was the first to properly separate the interlocking watercourses into the watersheds of the Mississippi River and the Atlantic Ocean.

Guyot’s sketch is beautiful and informed, and it completely changed maps of that region. Equally remarkable is that the sketch and report was left relatively unknown in the library of the Coast Survey for several decade, rediscovered in the 1930s.

From Guyot’s perspective, the mountain region was also unique insofar as it contained a “negative axis” — a valley east of the Cumberland Mountains and west of the Appalachian Mountains. That valley of eastern Tennessee, he argued, had tremendous military value, and he urged the Union army that this was the best path to defeating the rebellion. It was situated in the heart of the South, yet because of its hostile terrain had been left fairly isolated from regions all around it. By occupying that region, the military might control the passes over the mountains to the east, which were connected to several major cities of the South. Finally, the valley of East Tennessee offered a path to the south (Atlanta, but also to the southwest) with no physical obstacles. Braxton Bragg might resist, but there would be no mountain ranges blocking the Army as it moved to capture railroad lines toward the Gulf. In this respect, the geology practically invited a military advance.

Guyot’s advice echoed Lincoln’s own vision of strategy for Tennessee. As early as 1861 the President had drawn attention to the loyalists of the region south of the Cumberland Gap, and repeatedly stressed the importance of building communication and transportation networks to the loyalists of Tennessee and western North Carolina. Other priorities came first in the first two years of the war, but by early 1863 such a strategy was developing, particularly with the Army of the Cumberland’s movement toward Chattanooga.

In September 1863, Lincoln gave his own mounted copy of the map to General Oliver Otis Howard, who had just been sent to aid Rosecrans and the Army of the Cumberland in Chattanooga. Pointing to the Cumberland Gap, Lincoln exclaimed to Howard “They are loyal there, they are loyal!” The detail of the Coast Survey’s map of this region must have fascinated Lincoln, and given him the cartographic evidence for what he already knew: that the diversity of the South–its landscape, topography, people, and sentiment–was ripe for exploitation.

My sincere thanks to John Cloud and Albert Theberge, who possess a commanding knowledge of the Coast Survey’s extraordinary work during the Civil War, and who shared the Guyot sketch with me.

Use controls to zoom and pan.

[…] through maps of data. Only a cartographic approach could help to explain why Eastern Kentucky and Tennessee had so many Republican counties, or why so many white Arkansans voted for Garfield in the 1880 […]